Slicking Up a Marlin 1894 .44 Magnum or I bought a "Remlin!"

by Roy

Seifert

Click here to purchase a zip file with this and

all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer: This

article is for entertainment only and is not to be used in lieu of a

qualified gunsmith. Please

defer all firearms work to a qualified gunsmith.

Any loads mentioned in this article are my loads for my

guns and have been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of these loads,

or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a

professional gunsmith, just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well

as a tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without the

assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this

article require special tools and cannot/should not be performed

without them.

Warning: Disassembling

and tinkering with your firearm may void the warranty.

I claim no responsibility for use

or misuse of this article. Again,

this article is for entertainment purposes only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark of

their respective manufacturers. Click on any

blue text to go to a

product/seller web site.

Introduction

I have several Marlin lever-action rifles in my collection:

-

1895CB .45-70 built in

2006

-

1894CB .45 Colt built in

2000

-

39A .22 S/L/LR built in

1947

-

336 .30-30 WCF built in

1976

I

wanted to add an 1894 .44 Remington Magnum to the list, but I was concerned

about quality. In 2008 Remington

Arms Company, Inc. acquired Marlin.

The story goes that the tooling was worn out, and since the Marlin staff was let

go, the technical knowledge was not passed on to Remington.

For about 4 years Marlin lever-action rifles built by Remington had many

quality problems. Poor fit and

finish, misaligned barrels, cycling problems, etc.

After their teething problems, the quality of Remington-built Marlin

rifles greatly improved. This rifle

I purchased is brand new, and I’m pleased to report it doesn’t have any of the

problems the early Remington-manufactured Marlins had.

In fact, I think it’s better than some of my other JM Marlin lever-action

rifles! As of the date of this

article Remington has filed for bankruptcy, is restructuring as RemArms, and has

sold manufacturing of Marlin rifles to Ruger.

Initial Inspection

Despite the horror stories, I purchased a Marlin 1894 .44 Magnum rifle.

It came with a California-mandated lock, and to my surprise, an offset

hammer spur for use with a scope! I

was very pleased with the overall fit, finish, and quality of this rifle.

The action was stiff, which was to be expected with a new rifle, but it

loaded and cycled dummy rounds perfectly.

The loading gate opening was smoothed and did not bite my thumb nor

scratch brass when loading cartridges.

The bluing was beautiful and matched my other Marlin lever-action rifles.

The trigger pull was crisp with just a hint of creep and broke at a

little over 4 pounds.

Based

on my research, this rifle may have been manufactured in June of 2019.

There are two letters stamped on the left side of the barrel in front of

the receiver: PN.

A post on the Marlin Firearms Collectors Association forum

http://www.marlin-collectors.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=25792 indicated the

following:

1st

letter = Month: B-Jan L-Feb A-Mar C-Apr

K-May P-Jun O-Jul W-Aug D-Sep E-Oct R-Nov X-Dec

2nd

letter = Year: E-2010 F-2011 G-2012

H-2013 I-2014 J-2015 K-2016

I

extrapolated that the letter N would be 2019.

Would a distributer keep a rifle in stock for over a year and a half?

Possibly, I really don’t know.

What’s important to me is that this rifle was built 10-years after the

Remington problems.

I did

find one minor fitment problem; the sling swivel stud on the butt stock was not

parallel to the rifle; it was crooked!

This is no big deal for me, I can turn it being careful not to split the

stock, but it’s this small attention to details that continue to plague

Remington. The stud was very loose

in the butt stock, so I added two white washers that come with sling swivel

studs to tighten it up. I didn’t

want to add epoxy to the threads in case I have to remove the stud someday.

Notice in the above photo that the stock was finished with the Marlin

bullseye in place which discolored the white.

Details, details, details!

Cycling the Action

As mentioned before, the action was a little stiff.

I sat in front of the TV watching movies and cycled the action a couple

hundred times driving my poor, patient wife crazy.

I could already feel the action getting smoother as the parts got

burnished and mated together. This

also put wear-marks on the bluing so I could tell where to polish or add

lubricant. I plan to polish the

internals and tweak the springs as I have done to my other Marlin lever-action

rifles (refer to my articles

Tuning the Marlin 1894 for Cowboy Action Shooting and

Building a Backpacker

“Scout” Rifle.)

I

noticed that when I pulled the trigger and let the hammer down slowly with my

thumb, the hammer rubbed against the trigger about 1/4-inch before striking the

firing pin. When I reduced the

full-cock notch on the hammer this problem went away.

When I closed the bolt there was a hesitation when it rode over the

hammer. Either the hammer or the cam

on the bottom of the bolt will need polishing and maybe recontouring.

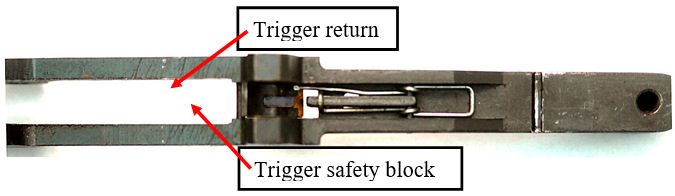

Working on the Trigger Safety Block Spring

NOTE: This process

must be performed first before adjusting the finger lever plunger spring.

I

removed the trigger guard plate from the bottom of the receiver.

I was pleased to find that all the screws on this rifle were installed

with Loctite blue. The trigger

safety block spring performs two functions; it activates the trigger safety

block (bottom leg in the above photo) and is the trigger return spring (top leg

in the above photo). This spring is

very stiff by design but can be lightened.

I used a dental pick and a small screwdriver to carefully bend up each

leg so there wasn’t so much tension on the trigger or trigger safety block.

Both still functioned as designed, but the trigger pull was lighter.

This was a trial-and-error process; each leg of the spring must still

provide tension.

Polishing the Internals

To my surprise, I had to do very little polishing to improve the action.

I was very pleased and impressed by the amount of polishing already

performed on this rifle.

The

finger lever plunger keeps the lever in place when the action is closed and

prevents the lever from opening when loading cartridges.

The two angled surfaces were somewhat polished but still had some tooling

marks. This was much better than

other Marlins I own. I removed the

pin that holds the plunger in the lever.

Note how this pin comes out; it must be reinstalled exactly as it came

out. One side of the plunger is flat

for the retaining pin that prevents it from coming out during operation.

I polished the two angled surfaces with 400-grit wet/dry sandpaper placed

on a flat surface until the tooling marks were completely removed.

I used a 400-grit polishing stick to gently round the sharp edge at the

tip of the plunger. I oiled the

plunger and reinstalled it in the lever with a new spring (see below).

The

trigger safety block prevents the trigger from being pulled when the lever is

open and the bolt is out of battery.

When the lever is closed and the bolt is in battery, the trigger safety block is

depressed so the trigger can be pulled.

The finger lever plunger keeps the lever closed which keeps the trigger

safety block depressed, but its spring must be strong enough to overcome the

pressure of the trigger safety block spring.

If the finger lever plunger spring is not strong enough, the lever won’t

stay closed. Now that I have reduced

the tension on the trigger safety block spring, I can install a lighter finger

lever plunger spring.

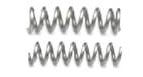

I

didn’t want to modify the factory spring (top), so I cut a length of 0.148-inch

outside diameter spring from Brownells compression spring pack #71

025-071-000 to the same length as the factory spring.

I then cut 1/2-coil at a time and installed it in the finger lever and

tested it until I got what I wanted.

The lever is now easier to open and close and stays closed when loading

cartridges.

The

spring on the ejector was already set from the factory so the ejector would not

put so much pressure on the bolt. I

used a Cratex bit to polish the tip that rides in a notch in the bolt.

The ejector notch in the bolt was already polished smooth so most of the

tool marks were gone.

After

cycling the action many times, I noticed two parallel wear marks on the face of

the hammer. These are two raised

areas on the hammer which reduce friction between the hammer and bolt when the

action is opened.

To

eliminate the hesitation from the bolt cam riding over the hammer when I closed

the action, I first removed the rear half of the firing pin from the bolt by

removing the rear roll pin. I used a

narrow 400-grit polishing stone to polish a bevel in the sharp edge in front of

the cam. I also polished the cam

with a Cratex bit. Now, when I close

the bolt, it slides smoothly over the hammer with almost no hesitation.

I reassembled the bolt and lubricated the top, bottom, hammer cam and

ejector groove with SFL-0 grease. I

didn’t perform any other polishing to the bolt because it already slid smoothly

in the receiver.

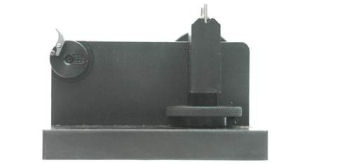

Working on the Sear

Caution, this work should not be performed without the proper tools to prevent

rounding the sear which could cause the rifle to become unsafe.

I

installed the Marlin 336 Adapter I purchased from MidwayUSA.com

#917687 on the Power Custom Series I Stoning Fixture I also purchased from

MidwayUSA.com

#743549. I adjusted the guide so

my 900-grit polishing stone was polishing the sear surface flat.

I polished the sear until it was mirror smooth, then applied Brownells

Action Lube Plus

#083-050-002 to the sear surface.

Action Lube Plus is my preferred lubricant for hammer and sear surfaces.

This

tool has been one of my better investments.

When I perform an action job on one of my guns, I purchase the

appropriate adaptor for the fixture.

This fixture has paid for itself repeatedly and has allowed me to remove creep

and smooth the action on many of my guns.

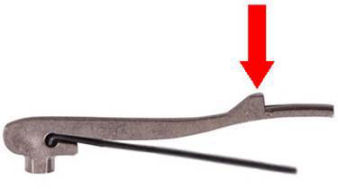

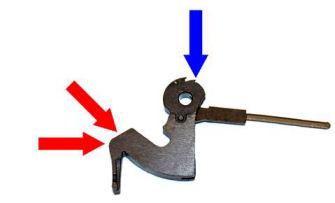

Working on the Hammer

The

hammer required a little bit of work to make it smoother, and to make the

trigger pull crisper. I used a

Cratex bit and my Dremel tool to polish the face and top curve of the hammer as

indicated by the red arrows in the photo above.

The full-cock notch (blue arrow) measured 0.030” which made the trigger

pull long with some creep. Using a

220-grit polishing stick, I reduced the depth of this notch to 0.018” which made

the trigger pull nice and crisp with no creep, but still safe.

I was careful not to reduce the depth of the notch too much, otherwise

the sear could contact the half-cock notch and break it when the hammer was

released. I applied Brownells Action

Lube Plus to the sear notch, FG-68 oil to the pivot pin hole and hammer strut

pivot, and Brownells Oxpho-Blue to the exposed metal.

After working on the sear and hammer, the trigger pull was crisp with no

drag and measured 3-pounds. This

also eliminated the problem of the hammer touching the trigger.

Lapping the Muzzle

When I

acquire a new or used gun, I always lap the muzzle.

This removes any imperfections in the crown and makes the rifling at the

muzzle nice and sharp which enhances accuracy.

I installed the .44-.50 brass muzzle lap from the Muzzle Lap Set I

purchased from Brownells

080-764-000WB in my drill and applied some 400-grit lapping compound to the

end. I touched the end to the muzzle

and with the drill running at about 500 rpm rotated the drill as shown in the

photo. I replenished the compound to

ensure the lap was cutting. After

about 3-minutes, I cleaned the compound from the muzzle and bore, and applied

Brownells Oxpho-Blue liquid

082-024-004WB to the exposed metal.

Replacing the Magazine Tube Follower

This rifle came with a hard plastic red magazine tube follower.

I’m sure it was made red so someone looking in the action could see that

the magazine tube was empty of cartridges.

I decided to replace the plastic follower with a brass one.

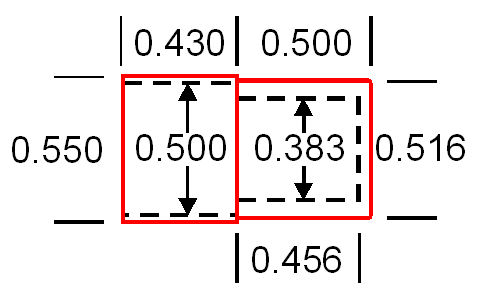

I

carefully measured the original follower and came up with the dimensions shown

in the above figure. I turned a

piece of 5/8” brass rod to the outside dimensions shown, then rounded off the

front edge with a file. I parted the

follower from the rod stock then turned it around in the lathe.

I used a 3/8” square end mill to hollow out the follower to a depth of

0.880”, then used a 7/16” square end mill to hollow out the rear to a depth of

0.430”.

I

removed the magazine tube plug screw and magazine tube plug being careful not to

let the magazine spring fly out and removed the barrel band screw.

I removed the factory plastic follower and replaced it with the new brass

follower. I cut 14 coils off the

magazine spring and reassembled the magazine tube.

The new follower works perfectly, and all ten .44 magnum cartridges feed

smoothly, even with heavy 310-grain bullets.

Replacing the Finger Lever Screw

There have been times when I had to disassemble a Marlin lever-action rifle in

the field but didn’t have any screwdrivers.

Because I shoot light loads in my Marlin 1894CB .45 Colt, the chamber

doesn’t seal completely so soot got down into the magazine tube and bound up the

follower during a cowboy match. I

had to disassemble the rifle and clean the magazine tube during the match.

I now carry a set of screwdrivers in my range bag, and after a range

session, I clean the magazine tube of any lever-action rifle I used.

The

magazine tube is often overlooked by shooters and never cleaned.

Powder residue attracts moisture which can cause the magazine tube to

rust. I purchased my .45-70 Marlin

1895CB and Winchester 1897 shotgun used, and both had rust in the magazine

tubes. Fortunately, I was able to

eliminate the rust and save both.

There

is a seller on eBay that sells a finger lever takedown screw that replaces the

factory screw. Instead of a flush

screw head that requires a screwdriver to remove, the head is wide and nicely

knurled so it can be removed by hand.

I removed the factory screw, oiled the shaft of the takedown screw, and

installed it finger tight. The part

fit perfectly and made disassembly for cleaning quick and easy.

I think I’m going to purchase one for all my Marlin lever-action rifles.

Adding

a Rear Peep Sight and Green Fiber Optic Front Sight

I never did like the semi-buckhorn sights that come on lever-action rifles.

I much prefer a peep sight, and so do my old eyes.

All my lever-action rifles except my 336 have

Marbles tang

peep sights installed. My 336

has a

Williams Ace in the Hole peep sight which comes with a Picatinny rail.

I decided to install a Williams Fool Proof receiver sight which has

micrometer click adjustments. I

don’t plan to use this rifle for cowboy shooting so it doesn’t matter what peep

sight I use.

I use

a peep sight as a ghost-ring sight because I seem to be able to pick up a sight

picture quicker with this arrangement.

I remove the aperture and use the large opening.

For fine or target shooting I replace the aperture.

I

purchased a

Williams FP 336 peep sight that came with two different styles of red fiber

optic front sights. This peep sight

is designed to be installed in the two rear scope mount holes in the receiver.

However, with the sight mounted in this location the aperture sits on top of the

hammer requiring installation of the offset hammer spur.

I really didn’t like the looks of this installation, so I decided to move

the sight forward on the receiver.

This meant I had to drill and tap an 8-40 hole in the receiver to accept a screw

in the forward mounting hole of the sight.

I

completely disassembled the receiver and removed the magazine tube and fore end.

I reinstalled the trigger guard plate so I wouldn’t crush the receiver in

my vise. I used two blocks of wood

to mount the receiver in my milling vise and leveled the top of the receiver.

I put painter’s tape on the wood so it wouldn’t mar the finish on the

rifle. I used wood blocks because

the receiver is not flat; there are two flares at either end for the stocks.

I centered the quill on the front hole of the two rear scope mount holes,

then moved the milling table 0.500-inch as measured with a dial indicator.

I used

a 1/8-inch square end milling bit to plunge-drill the hole, then finished with a

#29 drill bit. I tapped the hole

with an 8-40 tap, then removed all the swarf from the receiver.

To my surprise, there were no burrs on the inside of the receiver.

I completely reassembled the rifle and

put Loctite 242 (blue) on all the screws just like they did at the factory.

(Refer to my article

Using Loctite® Products.)

I

cleaned both mounting holes with acetone, then installed the sight and screws

with blue Loctite. I left the 8-40

plug screw in the rear scope mount hole.

Notice in the above photo the aperture does not interfere with the hammer

spur, and to me the installation looks cleaner and is more functional.

I realize mounting the sight in this position reduced the sight radius by

1/2-inch, but it is still longer than the barrel-mounted rear sight.

I have seen other people move the sight to the front two scope-mount

holes, but that would reduce the sight radius even more, but I like my solution

better.

Many

years ago, I purchased a Lyman #2 peep sight that I never used.

That sight came with three apertures: standard,

hunting and target. I no longer have

the sight, but I still had the target and hunting apertures.

These apertures have the same thread diameter and pitch as the Williams

FP sight. The hunting aperture is

short, so the knurling just touches the frame of the sight.

This is not a problem, but I probably won’t use this aperture.

I

purchased three bits from Brownells to fit the screws in the sight.

240-5 for the windage and elevation adjustment screws,

180-3 for the locking cam screw on the left side, and

120-1 for the small set screws.

I

needed something to use as a small screwdriver with the bits.

I took a 1/2” piece of brass round stock and drilled a hole in the center

with a #G drill bit. I pressed the

brass onto the hex portion of a hex bit extension.

I knurled the brass to make it easier to hold.

The screws in the sight don’t require much torque; they just need to be

finger tight. I carry the bits,

screwdriver, and apertures in a pouch attached to the sling (see below).

The

Williams sight came with two red fiberoptic front sights:

one for the Marlin 1894 and 336, and a longer one for the model 1895.

I never liked red because I seem to lose it in the background; I prefer

green. Many years ago, I purchased

both red and green 1/16” fiber optic rods from

OakridgeStores.com. I have yet

to use the red, but I use the green all the time.

I cut the red rod on the sight in half and removed the pieces from the

sight. I cut a piece of green rod

and inserted it into the front sight.

With 1/16-inch exposed from the rear I used a flame to melt the rod into

a ball being careful not to set the plastic rod on fire.

I clipped the other end so 1/16-inch was exposed and melted that end so

the rod was tight in the sight.

I

mounted the rifle in my padded vise and drifted the factory front sight out of

the dovetail from left to right. The

new sight was tight in the dovetail so I used a 65-degree dovetail file I

purchased from Brownells

#080-648-165WB to reduce the dovetail in the sight (not the sight base on

the rifle) until I could install the sight halfway into the dovetail by hand.

I installed the new sight from right to left and drifted it into the

dovetail until it was centered.

Making

a Sling Pouch

I

wanted to keep all my sight tools in one place, so I used some scrap chap suede

and made a small pouch that slides onto the sling.

The pouch is 2 1/2” x 2 1/2” and holds the spare apertures, mini

screwdriver, and bits. Now if I need

to adjust the Williams FP sight in the field, I have the tools handy.

Slugging the Bore

I thoroughly oiled the barrel and drove a pure lead slug through the barrel.

The barrel slugged at 0.431”.

.44 Magnum rifle barrels tend to be a bit larger than revolver barrels.

To shoot lead bullets accurately in this rifle they should be sized to

0.432”. SAAMI specifications show

.44 Magnum revolver barrels should be 0.429” and rifle barrels should be 0.431”.

This rifle will shoot jacketed bullets with no problems, but undersized

lead bullets can cause excessive leading and inaccuracy.

Searching for the Right Bullet Mold

I have

several .44 bullet molds in my collection but none of them would be accurate in

this rifle. In the above figure, from

left to right:

1.

Lee

429-255-SWC – This is a 255-grain semi-wadcutter (SWC) .429” bullet which is no

longer being produced by Lee. I

probably purchased this sometime in 1977 or 1978.

2.

Lee

429-240-2R – This is a 240-grain round nose (RN) .429” bullet.

I’m not sure why I purchased this or what I would use it for.

3.

Lee

C430-310-RF -This is a 310-grain wide flat nose (WFN) gas check .430” bullet.

4.

Lyman

429421 – This is a 240-grain semi-wadcutter .429” Keith-style bullet.

The

semi-wadcutter bullets have a sharp edge on the first driving band which could

cause feeding problems in this rifle, so I discounted those.

The round nose bullet would feed perfectly, but probably wouldn’t have

the best performance. The 310-grain

wide flat nose bullet would probably be the best choice, and I already know they

feed reliably in this rifle, but I see two problems with this bullet.

It is too narrow for this barrel, and even if I lapped the mold to expand

it, the gas check probably wouldn’t be wide enough to seal the bore.

I

thought seriously about modifying one of the cavities of the 310-grain WFN mold

by milling out the gas-check to the same diameter as the driving bands, then

lapping the cavity to increase the diameter.

Or I could mill away the gas-check and “Beagle” the mold.

Beagling the mold involves placing aluminum tape between the mold

cavities so the mold is wider thereby increasing the diameter.

Unfortunately, this causes the bullet to be out of round so I chose not

to do this. You can look up both

methods on YouTube.

For a

brief moment I also considered paper-patching my undersized bullets, but because

these would be loaded in a tubular magazine, and require a heavy crimp, loosely

crimped bullets would probably move back into the case, and heavily crimped

bullets would ruin or strip off the paper patch.

I also

thought about making my own bullet mold, but by the time I purchased all the

supplies I needed, I probably could purchase a ready-made mold for the same

price and avoid the labor. The

method for making a bullet mold can be found on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCh2TkMDcEo

Searching the Internet, I found

NOE Bullet Molds located in Provo, UT. They

produce a .434” 298-grain flat nose 2-cavity bullet mold that would work

perfectly for this rifle. The front

shoulder of the first driving band is not sharp so it should feed reliably, and

it is a plain-base bullet, so I don’t have to worry about a gas-check being too

small. I can size this bullet down

to 0.430” for my S&W 629 Trail Boss, or size it down to 0.432” for this rifle.

Oversize Gas-Checks

I wanted to add a gas-check to these bullets so I could shoot them at higher

velocities and not worry about leading.

Regular store-bought .44 gas-checks would be too small for this

plain-base bullet, so I decided to make my own 0.434” gas checks that would fit.

I found a video on YouTube by Dima Prok how to make your own gas check

forming dies:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rj4QUvSG7Ho&t=553s

He

refers to a set of plans that I downloaded from

CastBoolits.Gunloads.com.

Following the plans, I purchased some 7/8”-14 threaded rod and 1” 1045 steel bar

off eBay. The materials cost me

$30.00, whereas a prefabricated die would cost me $130+.

Inside the forming die is a post that I turned to 0.434” diameter.

I place a piece of aluminum or copper sheet in the slit in the forming

die, raise the ram of my single stage die so the cutter can cut a disc.

As I continue to raise the ram the disc is pressed against the post

forming the gas-check. A narrow

constriction inside the cutter strips the gas-check off the pin and prevents it

from falling back into the forming die.

Reaming a Lube/Sizer Die

Now that I have a .434” bullet mold, I needed a lube and sizing die to go with

it. I had a Lyman lube/sizing die in

0.430” which I opened up to .432”. I

tried doing this on my lathe, but this die is hardened, and I didn’t have a

carbide boring bit small enough to fit in the hole.

I cut

a slit in a piece of 3/8” wooden dowel to hold my sandpaper.

I cut a piece of 220-grit sandpaper, put one edge in the slot and wrapped

it around the dowel. I chucked the

die in my lathe and the dowel in the drill chuck in my tail stock and ran it

back and forth in the die. When the

grit became worn or full, I turned it around and used the other end.

When that end became full/worn, I folded the sandpaper in half and used

both sides. I continued reaming with

220-grit sandpaper until the diameter was 0.4315”.

I finished polishing with 400-grit wet/dry sandpaper until the diameter

measured 0.432”, and final polished with 600-grit wet/dry sandpaper.

I now have a bullet mold and lube/sizer die that matches this rifle.

Bore

Sighting

I load the NOE bullet with 18.4 grains of AA#9.

This is a maximum load that moves out at 1,300 FPS from a 7 1/2-inch

Ruger Blackhawk. From a 20-inch

barrel I estimate the velocity will increase to approximately 1,500 FPS so that

is the number I used for my calculations.

The

ballistic coefficient for this bullet is .253 so if this cartridge is sighted-in

at 100-yards, it will cross the line of site at 8-yards, which is 24-feet.

My indoor bore sight target is set at 25-feet, which means I only have to

adjust the sights so the laser dot is on the sight, not above or below it.

This

rifle comes with a folding semi-buckhorn rear sight.

I didn’t want to remove this sight so I adjusted it so the front sight

was touching the laser dot at 25-feet.

I folded down the sight and adjusted the Williams sight so the front

sight was again touching the laser dot.

This should at least get me on paper at 100-yards.

Summary

I once again would like to state how pleased I am with this rifle.

The fit and finish were beautiful, and it functioned right out of the

box, unlike the CBC Rossi 92 I purchased.

All the screws were installed with thread-locker to prevent them from

coming loose. I performed some minor

polishing and tweaking to smooth and lighten the action, but nothing like I have

done with other Marlin lever-action rifles in the past.

This is a working gun, not a cowboy action gun, so I wanted it to be

smooth and reliable.

|