Building

a Backpacker “Scout” Rifle

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers. All tools were

purchased from Brownells

unless otherwise indicated.

Introduction

Col. Jeff Cooper developed the scout rifled concept. His

definition of a scout rifle was a bolt-action with a crisp

3-pound trigger chambered for the .308 Win. cartridge. It

should weigh between about 6.5 and 7.5 pounds, with an

overall length of some 39.5 inches. It would feed from a

detachable-box magazine and have ghost-ring iron sights as

backup or reserve sights. Probably the most unusual feature

of Cooper's design was the forward-mounted, low-powered

scope. Although he said this was not mandatory, it would

preserve the shooter's peripheral vision, keep the ejection

port open to allow the use of stripper clips to reload the

rifle, and eliminate any chance of the scope striking one's

brow during recoil.

To

Cooper, the Scout was to be a general-purpose rifle for

hunting and personal defense. He didn’t care for the .223

Rem. cartridge, nor did he think the Scout Rifle needed more

power than the .308 Win. His idea was a short, compact

rifle that could successfully deal with targets up to about

200 pounds at whatever range the shooter could keep his

shots in an 8-inch circle, i.e. 2 minute-of-angle (MOA)

which is 2-inches at 100 yards, 4-inches at 200 yards, or

8-inches at 400 yards.

Cooper

felt a semi-auto rifle would work if the action were simple

and it met the weight requirement. I’m guessing that he

never considered a lever-action rifle because it didn’t take

a box magazine, and the lever would hit the ground when

cycling in the prone position. The tubular magazine of a

lever gun has a limited capacity, and can’t take spitzer

bullets because of the danger of setting off a round in the

magazine due to recoil. Hornady manufactures their

LEVERevolution® cartridges using their FTX® bullets. This

Flexible Tip eXpanding bullet has a better ballistic

coefficient than a typical .30-30 round nose bullet, which

makes it more accurate, and the soft tip makes it safe to

load in a tubular magazine.

However,

the lever-action is faster than a bolt action, and although

limited in capacity, the magazine can easily be topped up.

Some of the newer lever-action rifles manufactured by

Henry can only be loaded from the front of the magazine

tube like a .22 which makes them more difficult, but not

impossible to top up.

Marlin

336 .30-30

Being a

big fan of lever-action rifles, I decided to build a

backpacker scout rifle. I found a used Marlin 336 on

Gunbroker.com for a mere $300. With shipping and my FFL

dealer’s transfer fee the total came to $348, which I

thought was a great price. I’ve seen these rifles in pawn

shops and in used rifle racks as low as $200.

As soon

as I had the rifle in my shop I took it apart to do an

inspection. The rifle came with quick-detach sling swivels

and a leather “cobra” sling. According to the table at the

end of this article, this rifle was built in 1976 which

makes it a pre-Remington “bicentennial” rifle.

Fit and

finish of this rifle were excellent, except for a sliver of

wood missing from the wrist of the butt stock where it met

with the receiver. Although this was disclosed by the

seller, I plan to replace the butt stock with a synthetic

butt stock. The wood had some dings and scratches from

normal wear, which was to be expected.

The

action was smooth; with the hammer down I could work the

action with one finger. Using my trigger pull gauge, 8.5

pounds of force were required to lever the action. My

extensively reworked 1894CB only requires 3.25 pounds of

force to lever the action. I realize the 336 has a heavier

bolt, but I can certainly get that 8.5 pounds down.

The

trigger had some creep and was rough, but broke at 5.5

pounds. The bore was bright and clean with no signs of wear

or corrosion. The rifle was very dry, probably from sitting

in a gun safe or cabinet, but overall the rifle appeared to

have been well cared for with no signs of rust, but not used

very much. It also appeared to have never been worked on

because all the parts still had bluing except where they

rubbed together during normal use.

To my

surprise, this rifle did not have the cross-bolt safety;

that was not added until 1984. To carry the rifle safely

with a loaded round in the chamber I would have to carefully

place the hammer into the half-cock position like other

shooters have done for over 100 years. Another interesting

quirk about this rifle, the butt stock did not have the

signature bullseye because someone removed it and installed

a sling swivel stud with epoxy and/or plastic wood.

Build

Plan

To build my backpacker scout I plan to perform the

following:

·

Polish

and tune the internals and perform a trigger job

·

Cut the

barrel to 16.5-inches – 16-inches is the minimum legal

length for a rifle barrel

·

Cut the

magazine tube to match the cut barrel

·

Install a

synthetic youth butt stock so it fits my shoulder better

·

Convert

it into a takedown rifle like I did to my Rossi ’92 (refer

to my article

Building a Lever-Action Takedown Rifle).

·

Add a

scout rail to the barrel

·

Apply a

camouflage pattern using spray paint

·

Add a

scout scope or red dot sight to the rail

·

Add

backup ghost sights to the receiver

I found a

Marlin 336Y youth model on Gunbroker.com for $300 dollars,

but I was afraid it was built by Remington and I didn’t want

to spend time attempting to repair a poorly built rifle.

The youth model comes with a 16.5-inch barrel and a shorter

butt stock, but I wanted to do the gunsmithing myself.

Polishing

Tools

A word about polishing – I read many gunsmiths say to just

polish and not remove any metal. Polishing, by its very

nature, removes metal. In most cases, the goal of polishing

is to remove burrs, high spots, and tooling marks, but not

alter the shape of the part. I used the following tools to

perform the polishing work:

·

400 and

600-grit polishing sticks – available from

Boride Engineered Abrasives. They make a gunsmithing

kit with coarse and fine, wide and narrow polishing sticks

that I have used on many guns. Oil is used to clean these

polishing sticks.

·

Fine

Arkansas stone – available from Brownells. They make a

4-stone set

#975-104-000 that comes in different shapes perfect for

gunsmithing use. Oil is used to clean these stones.

·

Ceramic

Polishing Stones, Black Medium-Fine

#080-721-604 White Extra Fine

#080-721-601 – Available from Brownells used to polish

the sear. Water is used to clean a ceramic stick.

·

400 and

600 grit wet/dry sandpaper – Available at most hardware

stores. When placed on a flat surface, or wrapped around a

dowel or flat stick I use this to polish large areas.

Working

on the Bolt

To begin

slicking up the action I worked on the bolt first. I ran a

220-grit polishing stick in the ejector groove to remove the

milling marks. I polished again with a 400-grit stick, then

finished polishing the groove with 600-grit wet/dry sand

paper wrapped around a flat stick.

I then

polished the channel in the bolt where the tip of the lever

rides with a 400-grit stick. I polished the inside edges,

and removed the burrs from the outside edges.

Many

gunsmiths or tinkerers reduce the hammer face so the bolt

doesn’t have to exert so much pressure on the hammer

spring. I use a slightly different method as described in

Accurizing the Factory Rifle by M. L. McPherson. I

used a blue marker to color the underside of the bolt where

it rides on the hammer. I cycled the action a few times so

I could see the wear mark. This highlighted the camming

surface that cocks the hammer when the bolt is levered to

the rear.

I used my

milling machine and milled off most of the camming surface

leaving about 1/8”. This reduced the amount of surface area

riding on the hammer, which reduced the amount of pressure

riding on the bolt.

I used a

Cratex tip and my Dremel tool to polish the cam so it would

ride smoothly over the hammer. This surface was rough from

the factory and needing some smoothing.

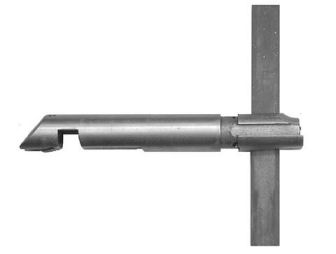

Finally,

I used a 400-grit polishing stick to polish off the high

spots from the inside of the locking bolt channel. I was

careful not to change the dimensions of this channel because

I still wanted the locking bolt to fit properly. In the

photo above you can see where I have begun to remove some of

the high spots.

Polishing

the Firing Pin

I disassembled the bolt to work on the firing pin. The bolt

comes apart with two roll pins. To get to the front roll

pin I had to remove the extractor by prying it from the

bolt.

The top

of the lever rubs against the firing pin in two places; the

front cutout as indicated by the worn bluing in the above

photo, and the front edge of the notch as indicated by the

arrow. I polished both areas with a 400-grit polishing

stick.

Sticky

Bolt

After reassembling the bolt, I discovered the bolt was

dragging in the receiver. I found that in the process of

disassembling the bolt I had bent one of the legs of the

extractor so it wouldn’t sit completely down in the

extractor cutout. It was raised just enough to drag on the

inside of the receiver.

I removed

the extractor and bent the two legs closer together. This

applied more pressure on the bolt, which allowed the

extractor to sit completely down into the cutout in the

bolt. The bolt now slides freely in the receiver.

Working

on the Ejector

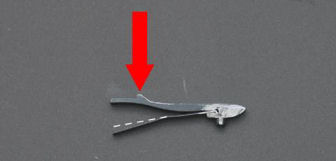

I

polished the sides of the ejector by rubbing them on

600-grit wet/dry sand paper placed on a flat surface. I

used a Cratex tip and my Dremel tool to polish the tip that

rides in the groove in the bolt. After polishing I

cold-blued the ejector with Brownells Oxpho-Blue Creme

#082-124-004.

I bent

the ejector spring just a bit as indicated by the dashed

line in the above photo. This was so the ejector wouldn’t

put too much pressure on the bolt. After bending the

spring, the bolt rode more smoothly in the receiver, and the

ejector still ejected cases properly.

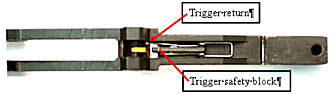

Working

on the Trigger Safety Block Spring

I removed

the trigger guard plate from the bottom of the receiver.

The trigger safety block spring performs two functions; it

activates the trigger safety block (bottom leg in the above

photo), and is the trigger return spring (top leg in the

above photo). This spring is very stiff by design, but can

be lightened. I used a dental pick to carefully bend up

each leg so there wasn’t so much tension on the trigger or

trigger safety block. Both still functioned as designed,

but the trigger pull was much lighter. This was a trial and

error process; each leg of the spring must still provide

tension.

Working

on the Sear

Caution, this work should not be performed without the

proper tools to prevent rounding the sear which could cause

the rifle to become unsafe.

Ok, with

the necessary disclaimer out of the way let’s talk about

trigger pull. There are primarily three things that affect

the weight of trigger pull; trigger return spring tension,

hammer spring tension, and the sear engagement angle with

the hammer. The trigger return spring tension can be

reduced by replacing the spring, bending the spring, or

cutting coils. As mentioned before, I carefully bent the

leg of the trigger safety block spring that acts as the

trigger return spring to reduce spring tension.

The

hammer spring, or mainspring, forces the hammer notch

against the trigger sear. The heavier the spring, the more

pressure is placed on the sear, which requires more pressure

on the trigger to release the sear. A lighter hammer spring

can lighten the trigger pull, but as you will see, I

installed a factory hammer spring. A perfectly smooth, flat

sear with the proper angle can go a long way to reducing the

amount of pressure necessary to release the sear.

I wanted

to polish the sear to get it glass smooth and flat which

would eliminate any gritty feel. I also wanted to change

the angle just a bit to lighten the trigger pull. I

disassembled the trigger guard plate assembly and removed

the sear by drifting out the pin holding the trigger and

sear in place.

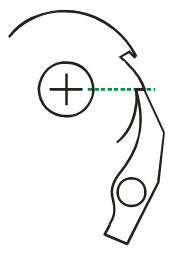

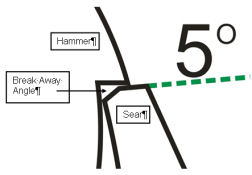

As

mentioned before, the hammer and sear mating surfaces should

be flat and square so the entire surfaces meet. I’ve worked

on some Marlin sears that were ground crooked so only one

edge mated with the hammer. They should also be in line

with the center of the pivot point of the hammer as shown by

the green line in the above diagram.

Trigger

pull can be increased or decreased by changing the angle of

the sear. Changing the angle in the direction of the green

line increases trigger pull. Changing the angle in the

direction of the red line decreases trigger pull. This must

be done carefully; if the sear is cut too much in the

direction of the red line the hammer can slip off the sear

and cause an unsafe condition.

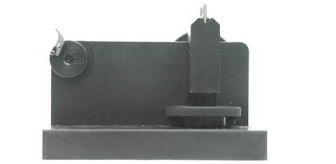

I already

had the Power Custom Series I Stoning Fixture

#743549 and purchased the Marlin 336 Adapter

#917687; both came from MidwayUSA.com. I installed the

adapter onto the fixture, and installed the sear onto the

adapter. I marked the sear surface with a blue marker and

adjusted the guide so my black, medium-fine ceramic stone

was polishing the sear surface flat.

I

adjusted the guide up 20 clicks to change the angle of the

sear by 5-degrees to make the trigger pull lighter. The

adjustment screw is a 7/16-16 screw, which is 16 threads per

inch (TPI). The adjustment wheel has 4-clicks per turn.

One click is about 1/4-degree of change, one full turn of

the wheel is about 1-degree of change, so 20-clicks is 5

full turns, which is about 5-degrees of angle.

I used a

400-grit polishing stick to cut the new sear angle, then

used the black medium-fine ceramic stone to polish the new

sear surface. I finished polishing with the white,

extra-fine ceramic stone until the sear surface looked like

a mirror.

After

changing the sear angle, I reversed the sear in the jig and

ground a break away angle in the rear of the sear. This

causes less of the sear to contact the hammer further

reducing trigger pull.

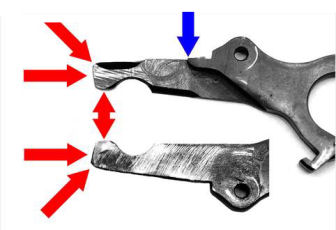

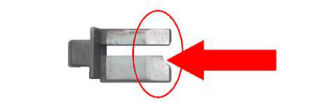

Working

on the Finger Lever

Each side

of the top of the finger lever had rough tooling marks and

worn bluing where it was rubbing on the inside of the bolt

and the carrier. I polished both sides with a wide 400-grit

polishing stick. I didn’t remove all the tooling marks, but

I polished just enough to remove any burrs and high spots.

I rounded the sharp edge shown by the blue arrow in the

above photo which helps to prevent the rifle from jamming.

If left sharp, this edge can cut into the carrier, which can

cause jams.

I used a

Cratex bit to polish the end of the lever as shown by the

red arrows in the above photo. These areas ride against the

inside of the bolt and firing pin.

The

finger lever plunger keeps the lever in place when the

action is closed. The two angled surfaces were rough and

had tooling marks. I removed the pin that holds the plunger

in the lever and polished the two angled surfaces with a

400-grit polishing stick until the tooling marks were

completely removed. I reinstalled the plunger with a Wolff

reduced power finger lever plunger spring

#33105. Some folks cut coils off the spring instead of

replacing it, but if the spring is too weak it won’t hold

the lever closed.

Replacing

the Hammer Spring

When I

disassembled the rifle, I discovered a previous owner had

replaced the factory spring with a Wolff reduced power

hammer spring

#32501. I read an article on the Internet that stated

reduced power hammer springs can cause erratic ignition,

which can cause accuracy problems. After performing all the

polishing, I replaced the reduced power hammer spring with a

factory spring. The action was much smoother, and I could

easily cycle the action with the rifle on my shoulder.

Working

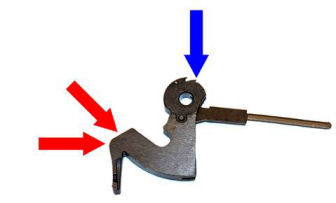

on the Hammer

The

hammer required a little bit of work to make it smoother,

and to make the trigger pull crisper. I used a Cratex bit

and my Dremel tool to polish the face and top curve of the

hammer as indicated by the red arrows in the photo above.

The full-cock notch (blue arrow) measured 0.030” which made

the trigger pull long with some creep. Using a 400-grit

polishing stick, I reduced the depth of this notch to 0.018”

which made the trigger pull nice and crisp with no creep,

but still safe. I was careful not to reduce the depth of

the notch too much, otherwise the sear could contact the

half-cock notch and break it when the hammer is released.

After working on the sear and hammer, the trigger pull was

crisp with no drag and measured 2-pounds. 6-ounces.

Polishing

the Locking Bolt

I didn’t

do much polishing on the locking bolt since it already slid

smoothly in the receiver. Using a 400-grit polishing stick,

I polished the sides to remove the high spots and burrs, and

polished the front where it impacted the bolt. I used a

Cratex bit to polish the indentation where the rear firing

pin rides.

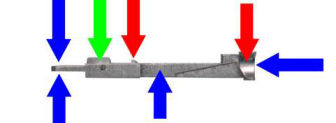

Polishing

the Carrier

I

polished the front and top of the carrier where the

cartridge cases ride, and the sides where the pivot screw

hole is located with a 400-grit polishing stick (blue

arrows). I polished the concave area where the cartridges

ride into the chamber, and the tip of the carrier rocker

with a Cratex bit (red arrows). Finally, I polished the

sides of the carrier rocker by rubbing them on 600-grit

wet/dry sand paper placed on a flat surface (green arrow).

I cleaned everything off with brake parts cleaner,

lubricated the carrier rocker with grease, and reassembled

the carrier. I applied a small amount of grease on the flat

sides around the pivot screw hole, and in the hole itself

and reassembled the rifle.

Fabricating a Front Barrel-Band

One

problem I immediately noticed with this rifle was that the

magazine tube was pressing against the end of the barrel,

which would probably have a negative effect on accuracy.

Minimizing the amount of contact with the barrel should

provide some increase in accuracy. I believe the reason

Marlin did this was so the 6-40 barrel-band screw would fit

through the notches in the barrel and magazine tube to hold

the magazine tube in place. To accomplish this the front

barrel-band had to squeeze the magazine tube closer to the

barrel, which caused it to touch the barrel. This also put

some tension on the magazine tube.

With the

front barrel-band removed you can see that the magazine tube

is straight and not touching the barrel. The gap measured

0.090”. The rear barrel-band screw doesn’t even touch the

magazine tube, which will make it easy to move forward for

disassembly once I convert the rifle into a takedown.

I decided

to fabricate a new front barrel-band for two reasons; one

because I plan to cut the barrel down to 16.5 inches so the

original front-barrel band won’t fit because of the barrel

taper. I could ream the barrel-band, but it will sit back

too far from the end of the muzzle for my purposes. Reason

two, the front sight will be an integral part of the new

barrel-band. I won’t have to drill and tap the barrel for

the factory ramp, therefore, the new barrel-band can set

closer to the muzzle. This allows me to fabricate a shorter

magazine tube plug, which saves some usable capacity in the

magazine tube. The new barrel-band won’t squeeze the

magazine tube close to the barrel; the tube will be

straight, which will eliminate any stress or flex making it

easier to pull forward for disassembly, and it won’t touch

the barrel.

I

carefully measured the diameter of the barrel and the

magazine, and measured the distance between the bottom of

the barrel and top of the magazine tube at the location of

the new barrel-band. I increased the diameter of the

magazine tube hole so the magazine tube wouldn’t bind; it

must be able to move freely. I fabricated the new front

barrel-band out of 3/4” 6061-T6 aluminum. Everything was

the same as the barrel-band I fabricated for my

Rossi ’92 except I milled a contour to the sides instead

of leaving them straight.

I ordered

a Williams 336 WGRS Fire Sight set

#945296 from MidwayUSA.com. I replace the red

fiber-optic rod with a green one as I did on my

Rossi ’92. The photo above looks a little strange

because I haven’t cut the barrel and magazine tube yet.

Cutting

the Barrel and Magazine Tube

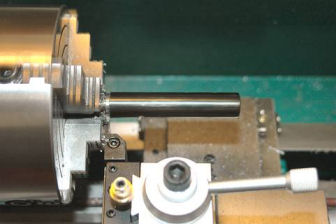

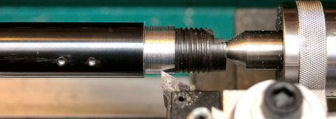

I chucked

the barrel in my lathe and used a cutoff bit to cut the

barrel down to 16 3/4“. Because of the configuration of my

lathe I couldn’t cut the barrel any shorter.

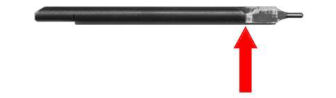

I then

used a 1/2” 79-degree crowning cutter

#080-586-500 with a .30-caliber pilot

#080-686-308 I purchased from Brownells to put an

11-degree crown on the barrel. I used plenty of oil to

lubricate the pilot and cutter. The above photo shows the

end of the barrel, the pilot, and the crowning cutter. The

cutter is pulled away from the barrel to expose the pilot.

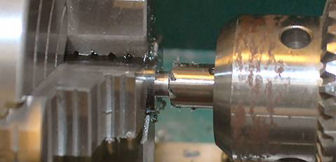

Finally,

I used a brass muzzle lap

#080-764-350 and 400-grit lapping compound to remove any

burrs from the muzzle. I put the lap into my variable speed

drill, applied lapping compound to the end, and with the

drill running at a slow speed, rotated the end of the lap in

the muzzle maintaining the angle shown in the above photo.

This makes the lands and grooves nice and sharp. I cold

blued the exposed metal with

Van’s Instant Gun Blue. I heated the barrel with a hair

drier and applied the cold blue until I got the deep

blue/black color I wanted.

Cutting

the Magazine Tube

I chucked

the magazine tube in my lathe and cut off the front so it

was 1/4” shorter than the shortened barrel. I measured the

location of the original hole for the magazine tube plug and

milled the new hole in the shorter magazine tube.

Here is

the shortened barrel and magazine tube. I’m not worried

about any scratches to the bluing because I plan to cover

the rifle with a camouflage pattern. The paint will cover

any imperfections in the bluing.

Installing a Synthetic Youth Butt Stock

My arms are not very long so I have to either cut the

buttstock or install a shorter one for a rifle to fit me

comfortably. I purchased a new Champion synthetic youth

model stock set

#78092 from ebay for a reasonable price. This is also

available from MidwayUSA

#330364. This youth model butt stock is 1 1/4” shorter

than the factory butt stock and comes with a recoil pad

installed.

This butt

stock fit very tightly onto the receiver. I used a Dremel

tool with a narrow grinding stone to relieve each channel

where the receiver tang and trigger guard plate set. I kept

the stone moving so I wouldn’t leave any hollows in the

plastic. When finished, the butt stock still fit snuggly

onto the rifle, but it was easier to remove and install. I

drilled out the butt stock screw hole with a 17/64 drill bit

so I could get the butt stock screw installed.

The

shorter butt stock fits me better, and makes it much easier

for me to lever the action. I could not install the

synthetic hand guard that came with the set because it is

mostly hollow. It needs to be solid to accept the adjusting

screws from the takedown spacer plate, so I will keep the

wooden hand guard.

Adding a

Sling Swivel Stud to the Lower Band

The newer model 336 rifles have a sling swivel stud mounted

to the lower barrel-band. Many years ago, I purchased a

package of 12 Uncle Mike’s® sling swivel studs #2516-0.

They come with a 10-32 x 1/8” threaded end. Apparently

Uncle Mike’s is no longer selling these, but a company

called GrovTec manufactures a similar item available from

MidwayUSA.com

#190531.

I

carefully marked the center bottom of the barrel-band and

milled a 0.159” hole, then tapped the hole with a 10-32

tap. I installed the stud with Loctite red for a permanent

attachment, then filed off the end of the stud until it was

flush with the inside of the band. The band fit perfectly

back onto the fore arm.

Fabricating the Magazine Tube Takedown Parts

I

fabricated the takedown parts the same as I did for my

Rossi ’92 based on the measurements I made for the 336.

I fabricated a new magazine tube plug out of 6061-T6

aluminum, and the takedown button out of 1/4“ steel round

bar. I milled a 3/16” semi-circle out of the bottom rear of

the new front barrel-band and into the magazine tube, then

milled a 1/4“ hole in the magazine tube plug. I staked the

end of the magazine tube so the follower wouldn’t fall out,

and fabricated a longer magazine tube follower out of

aluminum. With the new magazine tube plug in place in the

shortened magazine tube, and the new follower and shortened

magazine spring, I could still fit 5 cartridges in the

magazine tube, so I reduced the capacity of the tube by only

one cartridge.

Since

there is now nothing holding the magazine tube in place

other than the takedown button, when pulled forward for

takedown, the tube can come completely out of the rifle and

get lost. To prevent this from happening I installed a

magazine tube sling swivel stud just below the front

barrel-band. This stud also gave me something to hold on to

when moving the magazine tube forward.

To

prevent the magazine tube from moving too far backwards when

the rifle is disassembled, I installed a 6-40 filister head

screw in the magazine tube and magazine tube plug in front

of the new barrel-band.

Fitting

an XS Lever Scout Mount

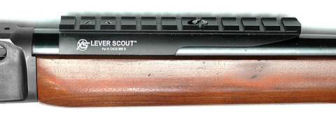

I found a

used XS Lever Scout rail with all mounting hardware on ebay

for $25.00 plus shipping. MidwayUSA has them for $63.90, so

I think I got a great price. Because I’m building a

takedown rifle, this mount cannot be attached to the

receiver.

The XS

Lever Scout rail mounts to the rear sight dovetail with a

dovetail pillar. The instructions state to sand or file the

bottom of the dovetail until the pillar fits into the

dovetail. I placed the bottom on a piece of 600-grit

wet/dry sand paper and briskly moved it back and forth. I

rotate the pillar so I wouldn’t be putting too much pressure

on one side or end. I tried for fit frequently, and sanded

until I could install the pillar into the rear sight

dovetail with finger pressure. I installed the rail onto

the barrel with the pillar screw and nut, and installed the

rear screws into the receiver.

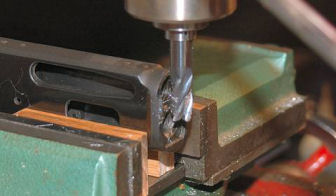

I removed

the butt stock, magazine tube, fore end and front

barrel-band from the rifle, then set it and leveled it in

the machinist vise on my CNC mill. I milled two holes to

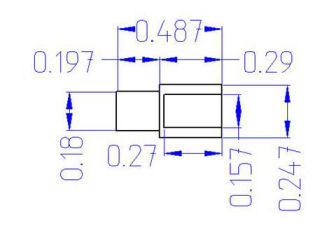

accept 6-48 filister-head screws in the locations indicated

by the red arrows in the first figure. The holes for the

screw shanks were 0.112” x 0.325” and were 1/2” apart. The

rail measured 0.192” thick and I wanted the depth of the

screw holes into the barrel 0.133”. The holes for the

filister heads were 0.212” wide by 0.115” deep. I located

the new mounting holes forward by 1/2” because the rear-most

flat of the rail was over the chamber and I wanted thicker

metal for the screw holes in the barrel.

After the

holes were milled I tapped the holes in the barrel with a

6-48 bottom tap and drilled out the center hole in the XS

rail with a #27 drill bit. I cut the rail at the 4th groove

from the rear with a hacksaw. I used a hose clamp to guide

the hacksaw blade. I squared the end with a file and

polished it with 400-grit wet/dry sand paper.

I

installed the rail onto the barrel using two 6-48 x 3/16

filister-head screws from the Pachmayr Master Gunsmith Screw

Kit I purchased from MidwayUSA.com

#967567; everything fit perfectly

Removing

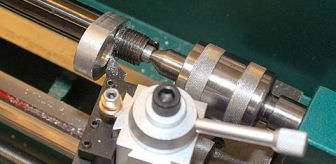

the Barrel

I made a

barrel vise bushing out of aluminum, installed the barrel

vise and bushing onto the barrel with rosin, and installed

the receiver wrench onto the receiver protected with tape.

The barrel came loose with a loud crack.

Milling

the Front of the Receiver

I set the

receiver between two oak blocks in my machinist vise and

squared the front. I used a 1/2” square-end bit to mill off

the lip from the front of the receiver. I removed 0.005” at

a time so the bit wouldn’t chatter or move the receiver in

the vise. When I got close to the receiver face I finished

by draw-filing with a bastard file until the lip was gone,

then polished with 400-grit wet/dry sand paper wrapped

around the file. I cold-blued the exposed metal with

Van’s Instant Gun Blue.

Milling a

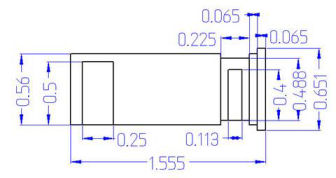

Step in the Barrel

I

fabricated a mandrel 1.000” long by 0.415” wide out of 1/2”

aluminum rod and used a centering bit to drill a V in the

end for my live center. I inserted the mandrel into the

chamber and mounted and centered the barrel in my lathe. I

turned a step in the barrel that measured 0.815” wide x

0.490” long. The spacer plate is 0.8135” for a press fit.

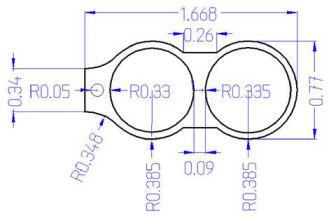

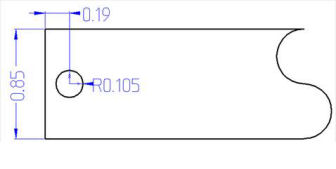

Fabricating a Spacer Plate

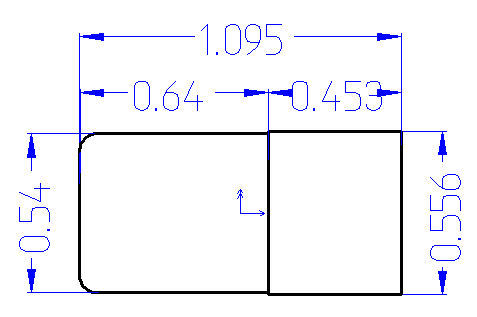

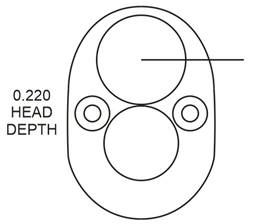

I carefully measured the barrel and magazine holes in the

receiver, the space between them, and the distance from the

top of the receiver. I enlarged the barrel hole to 0.8135”

and the magazine tube hole to 0.680”, but left the space

between them the same. The horizontal line extending from

the center of the barrel hole represents a scribe line that

will help me align the extractor notch in the barrel with

the plate.

I traced

around the receiver then scanned the outline into my

computer. I used CorelDraw 12 to create the drawing of the

spacer plate, which I exported to BobCAD-CAM v20 to create

the CAM code for my CNC mill. I milled the plate out of

1/2” 6061-T6 aluminum stock.

Installing the Spacer Plate

I heated

the aluminum spacer with a propane torch, and to my

surprise, it dropped freely over the step in the barrel with

no force required. I made sure the alignment mark I scribed

in the rear of the plate was in the center of the ejector

notch in the barrel. After the plate cooled it was nice and

tight on the barrel.

Fitting

the Spacer Plate

I faced

off the rear of the spacer plate until it fit tightly and

was properly aligned with the receiver. I made shallow cuts

0.005” at a time and installed the receiver frequently until

I got the proper fit. The final cut was only 0.002” to

achieve a tight fit.

I

polished the outside edge of the plate by shoe-shining with

400-grit wet/dry sand paper until it blended with the

receiver.

Cutting

and Installing the Fore End

I

measured from the fore end notch in the barrel to the front

face of the spacer plate at exactly 8-inches. I covered the

rear of the fore end with masking tape so the wood wouldn’t

splinter when cut, and marked the fore end 8” from the

barrel band screw hole. I cut the fore end to that mark.

I

installed the fore end onto the rifle and used a #21 drill

bit to drill through the holes in the spacer plate into the

fore end. I opened the holes in the fore end with a #9

drill bit. I tapped the holes in the spacer plate with a

10-32 tap and installed two 10-32 x 3/4” stainless steel cap

screws. The fore end sets nice and tight onto the rifle.

I rounded

the sharp edges left when I cut the fore end to blend with

the spacer plate, then sanded it smooth with 320-grit sand

paper.

Applying

a Camouflage Pattern with Spray Paint

I decided

to camouflage the rifle with spray paint.

Rust-Oleum® makes a line of flat camouflage spray paint

that can be applied to almost any surface. Amazon.com sells

a camouflage spray pack

#269038 consisting of two cans of forest green, two cans

of earth brown, one can of army green, and one can of

khaki.

From my

local Home Depot, I purchased Rust-Oleum self-etching gray

primer

#249322, moss green

#249071, rustic orange

#314753, satin hunter green

#7732830, and matte clear

#285093 spray paints. The primer will cover the entire

rifle, flat white will add texture to the sticks, and the

green and orange paints will provide additional autumn

colors to the leaves. Once the paint cures the matte clear

will protect the finish.

I got

some camouflage ideas by watching a few YouTube videos:

·

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jCGIE6dHFtg&t=331s

·

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z5RM-ihRawQ&t=331s#t=59.0098912

·

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgACuGtC3ow

·

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5z2hEWBUT8

·

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJNRGr7r5WY

I really

liked the first video where he used pine needles to make a

“sunlight in a dark forest” effect, which I decided to use

as my background. I also liked the sponge idea to add

texture.

I found a

small leaf stencil on the Internet which I printed onto a

sheet of paper and cut out. This stencil was for the small

orange and green leaves.

I masked

off the areas I did not want to paint. The hardest part was

masking all the holes in the receiver because I didn’t want

to get paint inside. I stuffed foam inside the receiver and

muzzle, and a wooden dowel in the bolt opening. I used

320-grit sand paper to rough up the wood, metal, and

synthetic parts, then cleaned everything with acetone. I

applied a thin coat of Rust-Oleum self-etching gray primer

to the entire rifle and allowed it to thoroughly dry. I

painted everything except the internal parts, screws, and

the lever. To me, the rifle with just the primer looked

ugly!

I laid

some pine needles onto the rifle and sprayed with bursts of

the khaki paint. I moved the needles so the resulting

pattern was not going in the same direction and sprayed

again with short bursts of khaki. After one side was

covered, I went back over the same side by laying the

needles in a different direction and spraying with the deep

forest green paint. After each layer of paint, I used a

hair dryer to speed up the drying process so I could apply

the next layer of paint.

I laid

the small leaf stencil onto the rifle and sprayed with army

green, or orange. After I dried the paint with a hair

dryer, I flipped the rifle over and did the same process

with pine needles, khaki and deep forest green paint, and

the small leaf stencil and orange shaded with earth brown,

and moss green shaded with army green to the other side.

After the

paint dried, I went over one side of the leaf with a darker

color because I wanted the leaves to have some shading. I

used army green on moss green, and earth brown on the orange

leaves.

I flipped

the rifle over and did the same process to the other side.

After the paint cured for about a week I applied two thin

coats of matte clear to protect the paint. After the clear

coat dried I lubricated and reassembled the rifle. I used

Loctite blue on all the screws to prevent them from becoming

loose.

Adding a

Red Dot Sight

Rather

than add a scout scope I decided to add a red dot sight.

Red dot sights are effective out to 100-yards, which is

probably the farthest I will be shooting this rifle. I

prefer the type of sight that is completely enclosed in a

tube because the tube prevents bright sunlight from washing

out the dot. Unlike a scope, a red dot sight has unlimited

eye relief, which means I can set it anywhere on the rail.

I found a TruGlo red dot sight

#TG8030A with a 5 MOA dot in a Realtree APG finish on

ebay for a very reasonable price with free shipping.

The knobs

that came with the sight were tightened with a supplied

metric allen wrench. Who is going to carry an allen wrench

in the field if you need to remove it and use the ghost ring

sight? I milled a 3/32” slot 0.140” deep in each knob so I

could use a knife blade, coin, or screwdriver blade from a

multi-tool pocket knife to remove the sight. A shot of

khaki and deep forest green covered the bright aluminum

cuts.

I am very

pleased with the finished result. I guess I should be

careful and not lay my rifle against a tree or I might never

be able to find it! One of my concerns is just how durable

the paint finish will be. I already discovered that Loctite

blue removes the paint, and it scratches easily, but time

will tell.

Adding a

Butt Cuff

MidwayUSA

sells a buttstock cover by Beartooth Products that comes in

Mossy Oak Break Up

#203692. It includes 5 foam pads of different

thicknesses to raise the comb to fit different shooters for

use with scopes or red dot sights. It also includes 6

cartridge loops for spare ammo.

Bore

Sighting

|

Bore Sight Calculator |

|

Sight Height (inches) |

Angle of Departure |

Sight Position @ 25'

(inches) |

|

1 |

0.063661951 |

0.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

Angle of Departure Calculator |

|

Sight Height (inches) |

Distance to cross line of sight (inches) |

Angle of Departure |

|

1 |

900 |

0.063661951 |

Laser

Bore Sight Data for Peep Sight

I used my

laser bore sight calculator to initially sight in both

the peep sight and the red dot sight. I used the data from

the Remington web site for their .30-30 170 grain Core-Lokt

cartridge. Remington states the muzzle velocity for this

load is 2200 fps with a ballistic coefficient of 0.254.

Using

Sierra Bullets Infinity version 6, with this load sighted in

at 100-yards and the 1-inch fiber-optic front sight, the

bullet would cross the line of sight at 25-yards. When I

entered this data into my calculator it showed that the

front sight would have to be 0.7-inches above the laser dot

at 25-feet, i.e. the laser dot would be 0.7 inches low with

the sights aligned with the center of the target. I

adjusted the receiver-mounted peep sight for this setting.

|

Bore Sight Calculator |

|

Sight Height (inches) |

Angle of Departure |

Sight Position @ 25'

(inches) |

|

1.84 |

0.06507666 |

1.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Angle of Departure Calculator |

|

Sight Height (inches) |

Distance to cross line of sight (inches) |

Angle of Departure |

|

1.84 |

1620 |

0.06507666 |

Laser

Bore Sight Data for Red Dot Sight

The

TruGlo red dot sight sets about 1.84-inches above the bore.

The bullet would cross the line of sight at 45-yards. Using

this data showed that the red dot would have to be

1.5-inches above the laser dot at 25-feet, i.e. the laser

dot would be 1.5 inches low with the sight aligned with the

center of the target. I adjusted the red-dot sight for this

value.

These

values should get my shots on paper at 100-yards. I started

at 50-yards and adjusted my sights to be 1/2"-low, which

brought my shots right on at 100-yards.

Summary

The takedown lever-action is not a new concept, although it

has been made popular by Wild West Guns with their Copilot,

which is a modified Marlin lever-action rifle. I converted

my Rossi ’92 .45 Colt rifle into a takedown rifle (refer to

my article

Building a Lever-Action Takedown Rifle) which was

based on the article A Takedown Rifle found in The

NRA Gunsmithing Guide – Updated published in 1982, so

the process has been around for a while.

After all the work was

completed and with the red-dot sight installed, the rifle

weighed 7.25 pounds; just under Col. Cooper's requirement.

Marlin

336 Year of Manufacture

The following table can be used to date the year of

manufacture of a Marlin 336. It is also valid for

determining most other Marlin firearm build dates from 1946

to the present.

Marlin

year of manufacture maybe determined from the following

table of letter/numeral prefixes to the serial number:

|

Date |

Prefix(s) |

|

|

Date |

Prefix(s) |

|

|

Date |

Prefix(s) |

|

|

1946 |

C |

|

|

1955 |

M |

|

|

1964 |

Y, |

Z |

|

1947 |

D |

|

|

1956 |

N |

|

|

1965 |

AA |

|

|

1948 |

E |

|

|

1957 |

P |

|

|

1966 |

AB |

|

|

1949 |

F |

|

|

1958 |

R |

|

|

1967 |

AC |

|

|

1950 |

G |

|

|

1959 |

S |

|

|

1968 |

AD, |

68 |

|

1951 |

H |

|

|

1960 |

T |

|

|

1969 |

69 |

|

|

1952 |

J |

|

|

1961 |

U |

|

|

1970 |

70 |

|

|

1953 |

K |

|

|

1962 |

V |

|

|

1971 |

71 |

|

|

1954 |

L |

|

|

1963 |

W |

|

|

1972 |

72 |

|

Starting

in 1973, the year of manufacture can be determined by

subtracting the first two digits of the serial number from

100: Example: SN 2512345 would have been made in 1975 [100 -

25 = 75].

|