Building a Lever-Action Takedown Rifle

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers. All tools were

purchased from Brownells

unless otherwise indicated.

Introduction

When I started Cowboy Action Shooting™ in 2000, my first

lever-action rifle was a Rossi ’92 SRC in .45 Colt. I

believe SRC stands for Saddle Ring Carbine, but my rifle

didn’t come with a saddle ring. Because so many other

shooters in our club had the same rifle I added the beads

and feather to the front sling swivel so I could tell which

one was mine when lined up in the rifle rack.

The Rossi

‘92 SRC is a modern copy of the Winchester model 1892

lever-action rifle; the iconic rifle used in many western

movies and TV series. My rifle didn’t have the

receiver-mounted safety or rebounding hammer; it was built

as John M. Browning had originally intended. I used this

rifle in cowboy matches for years, but retired it in favor

of a Marlin 1894 Cowboy in .45 Colt. The stock on my rifle

is pretty beat up from years of banging around in gun carts

and range racks, but I never could part with it because I

like the nostalgia and action of the rifle. Now it’s time

to have some fun and improve my gunsmithing skills by

converting it into a takedown rifle.

I found

two articles on the Internet on how to perform this

conversion:

http://rvbprecision.com/shooting/rossi-1892-winchester-take-down-conversion.html

http://www.homegunsmith.com/cgi-bin/ib3/ikonboard.cgi?act=ST;f=3;t=19176;hl=takedown

Both are

based on the article A Takedown Rifle found in The

NRA Gunsmithing Guide – Updated which I used as my

primary guide for this project.[i]

Unfortunately, all the articles left out some steps which I

had to improvise along with way.

Conversion Plan

To convert this rifle into a takedown rifle I performed the

following steps, some of which were not required for the

conversion, but were changes I wanted to make to the rifle:

1.

Fabricate a new front barrel-band with integral dovetail

(not required for the conversion)

2.

Install a front sight with green fiber optic rod (not

required for the conversion)

3.

*Fabricate a longer magazine tube plug

4.

*Fabricate a takedown button

5.

Mill the button hole in the magazine tube and front

barrel-band

6.

Clean the magazine tube (not required for the

conversion)

7.

Crimp the end of the magazine tube so the follower will not

come out when taking apart the rifle

8.

*Fabricate a longer follower (not required for the

conversion)

9.

Mill two notches in the magazine tube for the two

barrel-band screws so it can move forward

10.

Completely disassemble the rifle and unscrew the barrel from

the receiver

11.

Mill the front of the receiver flat and polish

12.

*Turn down a step on the barrel behind the threads

13.

Fabricate a spacer plate

14.

Press the spacer plate onto the barrel

15.

*Face off the rear of the spacer plate so it sits flush

against the receiver

16.

Fit the spacer plate to the receiver

17.

Modify the fore end so it will fit on the barrel and spacer

plate

18.

Install a large loop lever (not required for the

conversion)

19.

Finish the aluminum parts (not required for the

conversion)

20.

Refinish the wood (not required for the conversion)

21.

Install a tang peep sight (not required for the

conversion)

Lathe

*The

steps above marked with an asterisk required the use of a

lathe. I purchased a Grizzly G0765 7” x 14” bench-top lathe

which, with some modifications, worked very well for this

project. Purchasing my bench top mill/drill back in 2002

got me started into real gunsmithing, and the lathe will

further improve my knowledge, skills and capabilities. I

purchased a few books on how to use a lathe to help me

learn, and found some great “how-to” videos on You Tube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Za0t2Rfjewg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXET1-g6CJA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ue8XtStUBA

Front

Barrel-Band

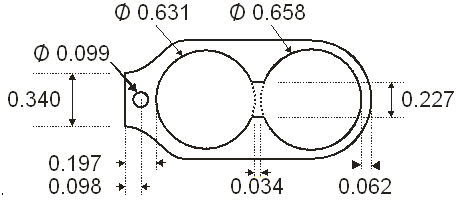

The original front sight was an integral part of the front

barrel-band and was narrow. I wanted to install a green

fiber-optic front sight, and quickly change out front sights

which is why I decided to fabricate a new front

barrel-band.

I carefully measured the diameter of the barrel and the

magazine tube holes in the original barrel-band, and

measured the distance between the bottom of the barrel and

top of the magazine tube at the location of the original

barrel-band. I increased the diameter of the magazine tube

hole so the magazine tube wouldn’t bind when the mounting

screw was tightened; it must be able to move forward. I

used CorelDraw 12 to produce the initial design for the new

front barrel-band, then exported the drawing to BobCAD CAM

v20 to produce the G-code for my bench-top CNC mill.

I fabricated the new front barrel-band out of 3/4” 6061-T6

aluminum. I then milled a 3/8” wide x 0.100” deep x

65-degree dovetail for the new sight using a 65-degree

dovetail cutter I purchased from Brownells

#080-621-305.

The dovetail cutter was only 0.300 wide, so I opened up the

dovetail by moving my milling machine table 0.037” on either

side of center, then finished with a 65-degree dovetail file

I purchased from Brownells

#080-648-165

so the sight would move freely. I drilled and tapped a 6-32

hole for a set screw in the front of the barrel-band to hold

the front sight in place. A drop of Loctite blue prevents

the screw from coming loose. By loosening the set screw, I

can easily change sights.

I drilled a center hole with a #43 drill bit through both

sides to accept a long, 4-40 hex-head screw. I tapped one

side with a 4-40 tap, and drilled the other side larger with

a #32 drill bit. I then used a 1/4” square end milling bit

to mill a countersink so the hex head would set flush with

the side. This screw mounts the barrel-band to the rifle.

I used my Dremel tool and a cutoff wheel to cut the end of

the screw so it wouldn’t protrude from the side of the band,

then polished and cold-blued the cut end.

Front Sight

I ordered a Williams Fire Sight 312M fiber optic front

sight from MidwayUSA

#865025.

This sight has a base width of 0.340” which was the

dimension I used for the top of the barrel-band, and length

of 3/4” which fit the new barrel-band perfectly. This sight

came with a red rod, which I hate because for me, red tends

to blend in with the background and disappear. Many years

ago, I ordered both red and green 1/16” fiber optic rods

from

Oakridge

Hobbies.

Although the package said 1/16”, they actually measured

0.060” which was the same size as the rod that came with the

Williams Fire Sight.

I used a razor blade to cut through the red rod in the

sight and removed each piece. I cut a piece of green rod

13/16” long and held one end close to a flame, not in the

flame. This created a ball of plastic at the end. I

inserted the end into the sight and cut the opposite end

1/16” away from the sight. I held the balled end of the rod

against the sight with my finger and held the straight end

close to a flame, again not in the flame, which created a

plastic ball on the opposite end. The two balls hold the

rod in place. I didn’t want to touch the flame to the

plastic rod because this would burn the rod and crystalize

the plastic which reduces its light transmission capability.

Cowboy Action Shooting™ rules do not allow fiber optic

sights so I also ordered a Williams 312M beaded front sight

from MidwayUSA.com

#358804.

If I want to use or loan my rifle for a cowboy match I just

switch out the sights. By the way, these sights came with a

tapered dovetail. I used the 65-degree dovetail file to

slightly straighten the taper so the sight would fit in the

dovetail in the barrel-band.

The original front sight measured 0.400” from the top of

the barrel. The Williams 312M sights measure 0.312” from

the bottom of the dovetail, but the sight itself measures

0.212”; the depth of the dovetail measures 0.100”. The new

sights now sit 0.409” above the barrel (0.197” barrel-band

plus 0.212” sight). To maintain the same sight height, I

would have needed a 0.303” front sight, but the Williams

sights only came in 0.290” or 0.312” heights. I decided to

go higher because I plan to install a Marbles tang peep

sight which I can adjust for the increased height of the

sight. Also, some of my heavier loads shoot high so I

needed the taller front sight. It’s usually easier to

adjust a sight higher than lower.

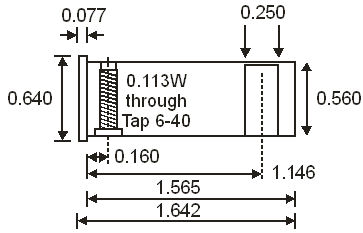

Magazine

Tube Plug

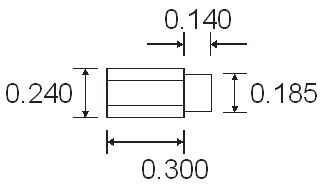

Before

doing any lathe work on the rifle barrel, I wanted to get

some practice to develop my skills. I had some 7/8” round

aluminum bar stock I had purchased from

OnlineMetals.com which I used to fabricate the new

magazine plug to the above dimensions. These were based on

the measurements for my rifle with the new front barrel-band

in place. The 6-40 threaded hole at the front of the plug

is for the plug screw that holds the plug in the magazine

tube. The original screw protruded into a hole drilled into

the barrel to prevent the magazine tube from moving or

rotating, but this will no longer be needed because of the

takedown button. The original screw had a 6-48 thread, but

I didn’t have a 6-48 tap, so I used 6-40 instead.

The 1/4”

hole at the other end of the plug is for the takedown

button. This button protrudes from a hole in the magazine

tube and sets in a notch milled in the rear of the front

barrel-band and has two functions; one, it prevents the

magazine tube from rotating and moving forward when the

rifle is assembled, and two, when pressed it allows the

magazine tube to move forward for disassembly.

Even

though I did a lot of research on how to run a lathe,

because I had never used one before, my first magazine tube

plug was a throw-away, which I expected. As I got close to

the diameters I needed for my part, I neglected to measure

so they were undersized. The second plug I produced was

very accurate because as I got close to the diameter I

needed, I measured frequently and adjusted my lathe to cut

accordingly.

I

inserted the new plug into the end of the magazine tube and

marked the location of the screw hole with a felt-tip pen.

I chucked the plug into the rotary axis of my bench-top CNC

mill and located the center of the plug. I used a 3/32”

square end milling bit to plunge-mill half-way through the

plug at the location of the plug screw. I rotated the

rotary axis 180-degress and plunge-milled through the other

side of the plug. I then milled a countersink for the screw

head 0.200” wide by 0.055” deep.

I used a

#33 drill bit to ream out the hole, then tapped the hole

with a 6-40 tap. I didn’t tap completely through the hole

because I wanted to leave some metal for the narrow end of

the screw.

I

fabricated a new magazine plug screw from a 6-40 x 1-inch

fillister head screw. I used my Dremel tool with a cutoff

wheel to cut the screw, then used my lathe to remove the

threads from the last 1/3 of the screw and reduce the

diameter of the head. I polished and cold-blued the exposed

areas of the screw.

To modify

the screw, I fabricated a screw holder out of a piece of

scrap 7/8” aluminum rod. I used a #33 drill bit to drill a

hole through the center of the scrap, then milled a 1/4”

hole half-way through. I tapped a 6-40 hole in the

remaining half. I used this holder when I cut the end of

the screw, then chucked it into the lathe to remove the

threads. I turned the screw around in the holder and used

the lathe to turn down the head so it would fit in the

magazine tube.

I milled

a 1/16” wide slot 0.080” deep and 1/2” long in the front

face of the plug. This is for a screw-driver blade to

facilitate removal of the plug so I can clean the magazine

tube.

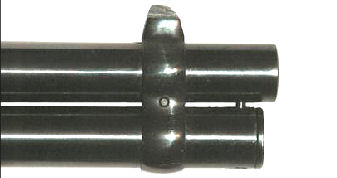

Takedown

Button

I turned

the takedown button from a piece of 1/4” aluminum rod, which

actually measured 0.243”. I plunge-milled a 1/8” hole in

the end, then opened it up with a #24 drill bit to accept a

0.125” OD x 5/8” spring from Brownells spring kit #69

#025-069-000. I made the front part of the button

0.002” smaller than 3/16” so I could use a 3/16” square end

milling bit for the button hole in the magazine tube and

front barrel-band.

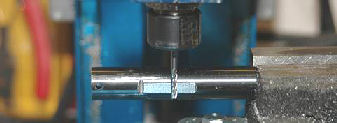

Milling

the Button Hole

I removed

the magazine tube from the rifle and installed the new

magazine tube plug. I wrapped a piece of tape around the

plug so it would fit tightly in the tube. I installed the

new barrel-band onto the magazine tube and tightened the

band screw so the barrel-band and plug would not move. I

mounted the band into my machinist vise, and centered a

3/16” square-end bit so it would mill a half-circle on the

bottom-rear of the barrel-band. I plunge-milled the button

hole in the front barrel-band and magazine tube with a 3/16”

square end bit and made sure I plunged at least 2/3 through

the plug.

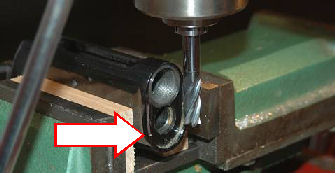

I removed

the plug from the magazine tube, and finished milling the

button hole to 0.250” x 0.530” deep. I inserted the button

and spring into the button hole and found that the front

wouldn’t sit flush with the plug. I removed 2 coils from

the spring and now it fit.

Above is

a photo of the completed plug and new screw next to a .45

Colt cartridge. You can see that the longer plug will

reduce the magazine tube capacity by one round, but I can

still load 10 + 1 making it suitable for cowboy shooting.

I

lubricated the button with a little synthetic grease,

inserted it into the hole in the plug, then inserted the

plug into the magazine tube until the button popped through

the button hole in the magazine tube. Everything fit

perfectly.

Cleaning

the Magazine Tube

When I removed the magazine tube to perform this work, I

discovered that it and the magazine spring were beginning to

rust. I took some 000 steel-wool and gun oil and ran it

over the spring and through the magazine tube to remove the

rust, then left both with a thin coat of oil to prevent

further rusting. I also cleaned leftover soot in the

receiver-end of the magazine tube and follower. This came

from shooting light, target loads that didn’t completely

seal the chamber.

After

shooting a rifle or shotgun that has a magazine tube, part

of my cleaning routine is to also clean and oil the magazine

tube and spring to prevent rust from forming. When I

purchased my Winchester ’97 shotgun the magazine tube spring

was rusted through in two places, and the magazine tube

itself had some heavy pitting due to rust from years of

neglect (refer to my article

Modifying a Winchester 97 for Competition).

Crimping

the Magazine Tube

The receiver end of the magazine tube must be crimped so the

follower doesn’t fall out and jam the rifle when being

disassembled. Only one of the Internet articles described

how to do this, and the NRA guide had no suggestion, so I

came up with my own idea.

I thought

the best way to accomplish this was to stake dimples in the

magazine tube. Using my new lathe, I made an anvil out of

7/8” aluminum rod. The anvil had three steps; the inner

widest step was the same diameter as the outside of the

magazine tube, the center step was the same diameter as the

inside of the magazine tube and prevented the tube from

crushing when I performed the staking, and the outer-most,

narrowest step allowed me to remove the anvil from the

magazine tube. The anvil fit into the end of the magazine

tube and had four grooves, one for each dimple. I milled

the four grooves to the same depth as the narrowest step.

These grooves allowed me to remove the anvil after staking.

I marked

the magazine tube 1/8” from the end. I placed the anvil

into the end of the magazine tube and used a prick punch to

punch a dimple on the line at the location of each groove.

I was surprised just how soft this metal was and how easy it

was to punch. After punching the four dimples I had to use

a rod to push the anvil out of the magazine tube.

The anvil

prevented the magazine tube from being crushed or bent

during the staking process, so the tube fit back into the

receiver with no problems. The four dimples now hold the

follower in place for disassembly.

Longer

Follower

The

original follower now set 1/8” deeper in the magazine tube.

Although this didn’t seem to affect function when I tested

the rifle with dummy rounds, I wanted the follower to push a

cartridge completely out of the magazine tube, so I turned a

new follower that was 1/8” longer than the original. (Man,

I’m having fun with my new lathe!)

I again

used a piece of 7/8” aluminum rod and turned the new

follower to the same diameters as the original. The inside

diameter of the original follower measured 0.455”. I

drilled out the center with a 29/64” drill bit which

measured 0.453”. This slightly smaller diameter didn’t seem

to make much difference; the magazine spring fit with just a

small amount of friction allowing me to remove the follower

just by pulling on the spring. I used a file to put a

slight taper on the front of the follower like the

original. The front of the new follower now extends

slightly out of the magazine tube as the original follower

did. I tested the rifle with dummy cartridges and they fed

with no problems.

Milling

Takedown Notches in the Magazine Tube

Normally,

the magazine tube is held in place by the two barrel-band

screws, and the magazine tube plug screw. To allow the

magazine tube to move forward for disassembly I cut the new

magazine tube plug screw short so it wouldn’t touch the

barrel. The barrel-band screws mate with two notches cut in

the barrel and magazine tube; the notches prevent the tube

from moving. Because I wanted the magazine tube to move

forward, I needed to extend the notches just in the magazine

tube. I did not want to extend the notches in the barrel

because I didn’t want the barrel-bands to move.

I found

that I only had to move the magazine tube one-inch forward

for the follower to clear the receiver. I set the magazine

tube in the machinist vise and used a 1/8” milling bit to

mill a one-inch notch 0.030” deep. I repositioned the tube

to mill the other notch to the same dimensions. I was

careful not to tighten the vise too much because I didn’t

want to crush or distort the fragile tube.

Once both

notches were milled I cold-blued the exposed metal and

coated them with oil. The notch looks rough in the above

photo because I didn’t polish the metal after milling. I

reassembled the rifle, tightened down both barrel-band

screws, and tested the magazine tube. When I pressed the

button, I could pull the magazine tube forward; sweet

success!

Rifle

Disassembly

I had no

problems disassembling the rifle since I had done it before,

but this was the first time I had removed the barrel from

the receiver. I fabricated an aluminum bushing for my

barrel vise so I could unscrew the barrel. I placed two

marks on the barrel 1-inch apart. The barrel measured

0.820” and 0.771” at the marks. Using my

barrel taper calculator, the barrel taper was

1.403-degrees. I have several bushings for different rifles

and handguns so I stamped the model on the receiver-end of

the bushing.

I put

masking tape on the receiver so the receiver wrench wouldn’t

mar the bluing, and installed the receiver wrench. Because

the receiver was square and flat I didn’t have to purchase a

special wrench. I sprinkled rosin I purchased from

Brownells

#083-016-100 on the inside of the bushing and inside the

barrel vise and installed the bushing onto the barrel. I

mounted the barrel vise in a well-supported bench vise and

removed the barrel. To get the extra leverage I needed to

unscrew the barrel, I used a 24-inch piece of steel pipe on

the handle of the receiver wrench.

Milling

the Front of the Receiver

To get the spacer plate to fit flush against the face of the

receiver I had to remove the lip that the fore end set in.

I cut two pieces of 1 x 2 wood, 3 1/2” long to serve as

spacers for the receiver. The sides of the receiver are not

perfectly flat; there are two flares at the front and rear

for the butt stock and fore end.

I mounted

the receiver in my machinist vise using the 1 x 2 spacers.

I used a 1/2” milling bit to remove the lip 0.010” at a

time. You can see in the above photo where I’ve started to

mill the lip and left a ledge in the untouched portion.

I milled

the lip until there were just a few thousandths left, then

used a flat bastard file to draw file the rest. I was

careful to keep my file flat so I would keep the face of the

receive flat.

I

polished the face with 400-grit wet/dry sand paper wrapped

around the flat file, then cold-blued the exposed metal.

The above photo shows the result. By the way, I’m using

Brownells Oxpho-Blue Crème

#082-124-004 for all my cold bluing.

Turning Down a Step on the Barrel

Because the bed of my lathe is a little less than 17-inches,

my 20-inch rifle barrel would not fit, therefore I had to

install it through the bore of the headstock. The headstock

has a 3MT (Morse taper) which allows material up to 0.780”

in diameter through the bore. My lathe came with a 3-jaw

scroll chuck, which means the jaws open and close together

with the chuck key. Unfortunately, the center hole of this

chuck is only 5/8-inches, which is not enough for the ‘92

rifle barrel.

I purchased a 5-inch, 4-jaw, independent chuck with adapter

plate from Little Machine Shop

#2346. The adapter plate allowed me to mount this large

chuck on my small mill. This is an independent chuck which

means each jaw works independently from the others, i.e.

each jaw is adjusted individually with the chuck key. The

scroll chuck is ok if I want to fabricate something from

scratch where I don’t care about runout, but the 4-jaw chuck

can be adjusted to eliminate runout, which is important when

working on the rifle barrel. The bore of this chuck is

1.180” which is larger than the bore of the headstock, so it

should be ok for a tapered rifle barrel.

Long work pieces, like a rifle barrel, need to be supported

at a minimum of two points to prevent it from wobbling. I

didn’t want to use the steady rest that came with the lathe

because it didn’t have bearings and I didn’t want to leave a

mark on the barrel. I fabricated a mandrel which fit into

the chamber of the barrel. In the rear of the mandrel I

drilled a 60-degree hole using a center drill for my live

center in the tailstock.

I fabricated another bushing that fit onto the barrel

9-inches from the chamber out of 3/4“ aluminum. The barrel

measured 0.690” and 0.684” at that point. Again, using my

barrel taper calculator, the taper came out to

0.229-degrees. With the bushing on the barrel and in the

4-jaw chuck, and the mandrel in the tailstock of the lathe,

the barrel was now supported at two points by the chuck and

the tailstock.

I turned down a step in the barrel that measured 1/2” wide

by 0.8155” in diameter. I’m using 1/2” aluminum bar stock

to fabricate the spacer plate. In the above photo, the step

does not look centered on the barrel. This is because the

barrel had a flat spot on the bottom so it wouldn’t

interfere with the magazine tube.

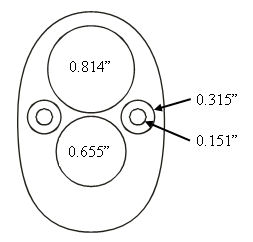

Fabricating a Spacer Plate

I traced around the face of the receiver, then scanned the

tracing into CorelDraw 12 to create a line drawing of the

outline. I carefully measured the receiver holes and placed

them accordingly in the outline drawing. I made the barrel

hole 0.814” in diameter so it can be pressed onto the barrel

flat. The magazine tube hole I made 0.655” in diameter.

The two holes on each side are for 10-32 hex-head cap

screws. These screws hold the fore end in place, and

provide adjustment if the spacer plate becomes loose over

time. The NRA article recommended using 1/4-20 screws, but

I thought they would be too large so I used 10-32 screws

instead.

I exported the line drawing to BobCAD-CAM v20, and from that

I created the G-code for my CNC mill. I milled the spacer

plate out of 1/2” 6061-T6 aluminum bar stock. Before

cutting out the plate, I marked the center at the top of the

plate. This helped me align the extractor groove in the

barrel to the top of the plate.

Pressing the Spacer Plate onto the Barrel

I heated the spacer plate with a propane torch and pressed

the plate onto the barrel using the barrel bushing I used to

remove the barrel from the receiver. Once the plate was

heated, I placed the bushing on top of the plate and used a

rubber mallet to strike the bushing and press the plate onto

the barrel. Each time I heated the plate I was able to

press it about 1/8”. After four cycles of heating and

pressing the plate was seated onto the barrel.

After the plate was seated I noticed the mark at the top of

the plate was not centered over the extractor groove in the

barrel. I again heated the plate with a propane torch and

used the mallet to rotate the plate on the barrel until the

extractor groove was centered on the mark in the plate.

Facing Off the Plate

The plate was thicker than the step on the barrel, which

meant the barrel could not rotate into the proper position.

To get the barrel to rotate to the proper position I needed

to remove metal from the remaining barrel shoulder and the

rear of the plate.

I set the barrel in the lathe as I did before and removed a

small amount of metal from the rear of the spacer plate. I

moved the tailstock out of the way and screwed on the

receiver to test for fit. I performed this remove metal and

fit procedure many times until the plate fit snuggly and was

properly aligned on the receiver.

Fitting the Spacer Plate

I wanted the spacer plate to fit flush with the edge of the

receiver. With the spacer plate properly aligned, I marked

the rear face with a blue marker and traced around the edge

of the receiver with a scribe. This left a mark in the blue

which corresponded to the outline of the receiver face.

I put tape on the barrel threads and on the barrel in front

of the spacer plate. I used a flat bastard mill file to

file the edge of the spacer plate down to the line. I had

to clean my file after 3 or 4 strokes to prevent the teeth

from becoming full and gouging the soft aluminum. After the

spacer plate was filed I used 400-grit wet/dry sand paper to

“shoe-shine” around the outside edge until it was polished

smooth.

Modifying the Fore End

I cut the

end of the fore end with my miter saw, then used my belt

sander to trim the end until it fit. I positioned the fore

end onto the rifle, then used a #21 drill bit to drill

through the adjusting screw holes in the spacer plate into

the fore end.

After I

drilled the holes in the fore end, I tapped the adjustment

holes in the spacer plate with a 10-32 tap. I tapped the

holes after drilling the fore end because I didn’t want to

damage the threads when drilling the holes. I installed two

10-32 x 7/8” stainless steel hex-head screws into the spacer

plate. As the screws mated with the fore end they tapped

threads into the wood. The fore end is now nice and tight

with these screws in place.

Installing a Large Loop Lever

My rifle originally came with a large loop lever which I

found difficult to operate quickly for cowboy shooting. I

replaced it with a standard lever which I could operate much

more quickly, but now I wanted to put the large loop lever

back on the rifle.

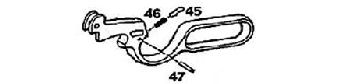

I used a

punch to remove the friction stud stop pin (47) from the

lever, which allowed me to remove the friction stud (45) and

friction stud spring (46) from the lever. I installed these

parts into the large loop lever, then installed the lever

into the receiver.

The

secret to using the large loop lever is to push your hand

forward so the loop rides along the front edge of your hand

which opens the action. Then close the action by pressing

the loop towards the butt stock as normal.

Finishing

the Aluminum Parts

I didn’t

want the bright aluminum parts to show, so I blacked the

aluminum with Birchwood Casey Aluminum Black. This product

works like cold-bluing for aluminum. I cleaned the parts

with acetone, then applied the aluminum black with a cotton

swab. I let the solution set for 60-seconds, then rinsed it

off with cold water. After the part was dry I sprayed it

with two coats a high gloss clear coat to protect the

finish. It doesn’t look like blued steel, but it does look

nice.

Refinishing the Wood

The butt stock and fore end had some sort of dark stain

which covered the beauty of the walnut. I used Bix paste

stripper to remove the old finish from the wood. I applied

4 coats of the stripper, then washed the wood with water and

scrubbed with a Scotch-Brite scouring pad.

After the

wood was dry I steamed out the dents using an iron and a wet

towel. This not only raised the dents, but it also raised

the grain. I used 400-grit wet/dry sand paper to smooth the

wood and remove the “feathers” that were raised by the

steaming process.

I allowed

the wood to completely dry overnight, then applied three

coats of Birchwood Casey Tru-Oil. I allowed the wood to dry

for 6 hours between each coat. Tru-Oil is my favorite

finish because it’s easy to apply, and if the wood gets

scratched or damaged, it’s easy to repair and apply another

coat. The butt stock is some sort of dark, “tiger” walnut.

As you can see in the above photo, you can now see the

beautiful grain and patterns in the wood.

I have

never been able to use a complete bottle of Tru-Oil because

once the bottle is opened and air gets in, it dries out. I

found a product called Bloxygen on Amazon.com that prevents

finishes like Tru-Oil from skinning over or drying out.

After I apply a coat of Tru-Oil, I spray some Bloxygen into

the bottle before closing the lid. Bloxygen works so well

that I have been using the same 8-ounce bottle of Tru-Oil

for years without having it dry out.

Installing a Tang Peep Sight

I won’t go into the details of installing a tang peep sight

to this rifle because I have already written an article

(refer to my article

Adding a Tang Peep Sight to

a Lever-Action Rifle). However, the Rossi

rifles use different tang screws depending on when and where

they were manufactured. My particular rifle requires a

10-32 x 1 3/4” tang screw to mount the peep sight. I

purchased a Marbles tang peep sight for a Rossi ’92 from

MidwayUSA.com

#140573. This sight also fits a Winchester ’94.

Apparently, the newer Rossi ’92 rifles require a M5-8 metric

tang screw, which is the screw provided in Marbles screw set

995002. This is the screw set Marbles says will fit the

Rossi. My older Rossi required a 10-32 x 1.75 tang screw so

a quick call to Marbles and they sent me the correct screw.

Conversion Completed

At this

point the conversion is complete. I replaced the sling

swivels on the magazine tube and butt stock with sling

swivel studs and quick-detach sling swivels which are very

convenient and easy to remove a sling from this take-down

rifle.

To

disassemble the rifle, I open the action, press the button

behind the front barrel band, pull the magazine tube

forward, and unscrew the barrel. To reassemble the rifle, I

open the action, screw the barrel onto the receiver until

the spacer plate is snug and aligned properly, press the

takedown button, and push the magazine tube in place until

the button locks in the notch behind the front barrel band.

Summary

After watching the Wild West Guns (WWG) TV series Wild

West Alaska and seeing their Copilot rifle, which is

nothing more than a converted Marlin, I wondered if I could

do the same conversion. My philosophy is if someone else

can do it, I can learn how to do it myself. The Copilot

does not have interrupted threads on the barrel and

receiver, which means you attach or detach the barrel with

multiple turns. I decided to do the same with my rifle to

reduce machining time. My Rossi ’92 requires 11 turns to

disassemble/assemble the rifle.

To

maintain the full magazine capacity of the original rifle,

WWG replaces the magazine plug screw with a thumb screw. I

personally don’t like that blob of metal hanging down below

the rifle; I think it detracts from the clean lines and look

of the original rifle, which is why I like the button plug.

As mentioned before, this reduced the capacity of my rifle

from 11+1 to 10+1, but that is acceptable and I can still

use the rifle for cowboy shooting.

.45 Colt,

or “Long Colt”, has always been my caliber of choice for

Cowboy Action Shooting™ and field use. Modern reloading

manuals provide recipes for more powerful loads approaching

or exceeding the .44 magnum suitable for use in Ruger or

Contender firearms. Some ammunition manufacturers are also

producing heavier loads in .45 Colt. The ’92 action is also

strong enough to handle these loads, which makes this

takedown conversion the perfect backpack companion.

The WWG

Copilot sells for $3,277 at the time of this writing.

Chiappa Firearms of Italy is building a series of ’92

takedown rifles which are imported by

Taylor’s and Company. At the time I wrote this article,

their prices started at $1,363 up to $1,483 depending on

what you wanted. A quick search of

Gunbroker.com shows Rossi ’92 rifles are available from

$300 to $600+. I think I paid $410 for my rifle new, plus

about $200 in upgrades for this project, the right tools,

some time and elbow grease and I have a neat takedown

rifle. This was not only a fun project, but I learned new

skills with my new lathe.

My rifle

did not have the same dimensions as the Winchester ’94 rifle

used in the NRA article; my rifle was a bit smaller. If I

was to perform this conversion on a different lever-action

rifle I would have to perform all the measurements over

again to ensure everything would fit.

Addendum

I decided not to refinish the rifle since I thought the

bluing already looked nice. However, I didn’t think the

painted aluminum matched the blued finish, so I decided to

re-make all the parts in cold-rolled steel so I could blue

them to match the rifle. I considered my aluminum parts as

practice, and made a few changes when I made the parts in

steel. I purchased the steel I needed from

OnlineMetals.com, which is my source for the steel,

aluminum and brass that I use for my projects.

As I

completed each part, I polished it with 400-grit wet/dry

sand paper then degreased it with acetone. For small parts

and touch-up I used Brownells Oxpho-Blue Creme

#082-124-004 to cold-blue the parts. I prefer the creme

because it sticks to the part. I heated the part in a small

toaster oven to 120-degrees Fahrenheit for 10 minutes, then

applied the Oxpho-Blue. I wiped it off after 60-seconds,

then buffed with #000 steel wool. After 3 or 4

applications, the parts took on a deep blue-black color that

closely matched the original bluing on the rifle.

For

larger parts such as the magazine tube plug and barrel-band,

I polished and prepared the part as before, then heated the

part in a small toaster oven to 120-degrees Fahrenheit for

10 minutes. I poured some

Van’s Instant Gun Blue into a plastic bowl and

completely immersed the part. After the part turned black,

I removed it from the solution, wiped off the excess bluing,

then buffed with #000 steel wool.

For the

steel spacer plate, I polished and prepared the metal. I

plugged the chamber of the barrel with a rubber stopper, and

blued the plate with Brownells Dicropan IM

#082-008-032. This is a rust-bluing process and

requires much time and many applications, refer to my

article

Refinishing a .45 ACP

Conversion Cylinder with Brownells Dicropan IM®.

The other

change I made was to drill and tap the top of the front

barrel-band to accept an 8-40 x 0.130 set screw I purchased

from Brownells

#080-534-002. I drilled a corresponding indent in the

barrel, but was careful not to drill completely through the

barrel into the bore. This set screw sets below the bottom

of the front sight dovetail which still allows me to change

sights. It prevents the front barrel-band from rotating on

the barrel, which I accidentally discovered would happen

with the aluminum barrel-band.

There’s

nothing like the look of blue steel and walnut. I’m glad I

didn’t try to refinish the rifle with any spray-on finishes,

and the new steel parts closely match the original factory

bluing. Next, I think I’ll try to convert a Marlin Guide

Gun in .45-70 to a takedown rifle. That should be an

interesting project.

[i]

Pete Dickey, “A Takedown Rifle,”

The NRA Gunsmithing Guide – Updated 1982, 273 -

276

|